The royal paulownia shows just how difficult it can be to uproot an invasive species.

By Mark Caskie

On the main trail at Haw River State Park in North Carolina, there is a long-since-abandoned farmer’s field. Last winter, just as I came to the field on a rise at its edge, I noticed a bare tree with unusual clusters of almond-shaped seed pods. I was so taken with them that I broke off a branched loaded down with the pods. While their dirty-brown color wasn’t attractive, I thought the half-open pods had an interesting graphic quality that might a good subject for a drawing. And when I shook the branch, the remaining seeds within the pods made a maracas-like rattle. I was delighted with my “found” rhythm instrument and drawing subject. I had no idea what kind of tree it was.

I never got around to making that drawing. Instead the branch with the seed pods remained on my carport for several months before I unceremoniously dropped it in the trash. I soon forgot about my trail-side find.

This fall I came across a small tree with enormous leaves in a wooded area in my neighborhood. The leaves seemed way out of the proportion to the size of the sapling, whose trunk was about as thick as my pointer finger. I picked one of the enormous leaves and I took it home to see if I could identify it using my field guide.

Identify it I did, and much to my surprise, I found the seed pods that I had collected last winter belonged to the very same tree as the giant leaf–royal paulownia (Paulownia tomentosa), a tree that ranks alongside kudzu, multiflora rose and mimosa as a serious invasive threat.

The coincidence of finding this tree twice in a single year led me down the proverbial research rabbit hole. The results of that search proved more illuminating than I could have imagined.

A Case Study

Royal paulownia offers a case study of how an invasive species can thrive and spread as a result of its ecological role as a pioneer plant combined with cultural factors such as its popularity as a garden plant and its rise as an unlikely cash crop.

Named after Anna Paulowna (1795-1865), the queen consort of The Netherlands and the daughter of Tsar Paul I of Russia, the tree now goes by a variety of other monikers including the princess tree, empress tree and foxglove tree.

Virginia has, unfortunately, proven to be fertile ground for the royal paulownia. Ironically, “fertile ground” for this tree means sterile ground as the result of fire or recently disturbed land. Given those parameters, the tree has been found to flourish in a variety of Virginia landscapes. Studies following Hurricane Camille in central Virginia in the late 1960s showed the tree thriving in debris avalanche fields. In another central Virginia study, royal paulownia was found well-adapted to riparian areas. A third study found it prospering in disturbed upland areas along with early successional species at sites in the Blue River Gorge in the Blue Ridge Mountains. And while not technically an invasive because it was planted, the current champion royal paulownia tree, according to American Forests, is in a cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. That tree is 57 feet in height, has a 64-foot crown and a circumference of 213 inches.

In Gardens and Plantations

The royal paulownia got its start as an invasive as packing material for Chinese porcelain exporters in the 1800s. Its soft, lightweight seeds often spilled out of those packages while in transit and spread the seeds along railroads tracks. Also, in the mid-19th century, the royal paulownia, which originates in central and western China, was exported around the world as an ornamental. From gardens and parks, it often escaped into natural areas, including in the eastern United States where it’s now completely naturalized.

While the royal paulownia has panicles of fragrant lavender flowers that resemble foxglove, for many gardeners the tree’s leaves are its main appeal. Royal paulownia, especially when young, has giant elephantine leaves. Gardeners often pollard the trees – cutting the branches back to the trunk – to force new denser foliage. This process results in massive leaves that can measure 24 inches or more across. Highly prized in many gardening circles, the royal paulownia has even been awarded the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit. The tree regularly appears in many gardening catalogs.

Royal paulownia is also highly prized in Japan for its wood. In earlier periods, a Japanese tradition encouraged families to plant a royal paulownia to mark the birth of a daughter. When the daughter grew up and was ready to marry, the tree was cut down and various items for her dowry were carved from the wood. The koto, the national instrument of Japan, is typically made from this wood because of its resonance and beautiful wood grain. Japanese craftsmen also use royal paulownia’s wood to create items such as gift boxes, bowls and furniture.

In the 1970s, a Japanese timber buyer took note of the naturalized royal paulownia growing in the United States, immediately recognizing an untapped timber market. This discovery led to a multimillion-dollar business because the slower-growing forest trees had growth rings that were close together, enhancing the wood grain. These older, naturalized trees in the forest were soon harvested but they left in their wake an interest in growing royal paulownia for profit. Agriculture Extensions in several states continue to promote the idea of growing royal paulownia on marginal land as a cash crop, even though there is virtually no domestic market for this wood.

Royal Paulownia as an Invasive

One of the qualities that draws the attention of would-be tree farmers to the royal paulownia is the same quality that makes it such a troublesome invasive. It’s the fastest-growing hardwood in the world, capable of growing as much as 20 feet in a single year. Theoretically, those would-be tree farmers can grow a harvestable crop suitable for some purposes in as little as 10 to 12 years. But as an invasive, this phenomenal growth means that this tree can outcompete most native plants.

That growth is just the beginning of its competitive advantages. Royal paulownia propagates through root sprouts, and a single tree can also produce as many as 20 million seeds a year, which are spread by wind and water. The tree’s ability to survive fire, cutting and bulldozing makes it difficult to control. Its tolerance of high soil acidity, drought and low soil fertility means it can find a foothold in just about any kind of marginal environment. Among those environments, it often colonizes rocky cliffs and disturbed riparian areas, where its aggressive spread and hyperactive growth may threaten rare and endangered native plants.

Royal Paulownia Revisited

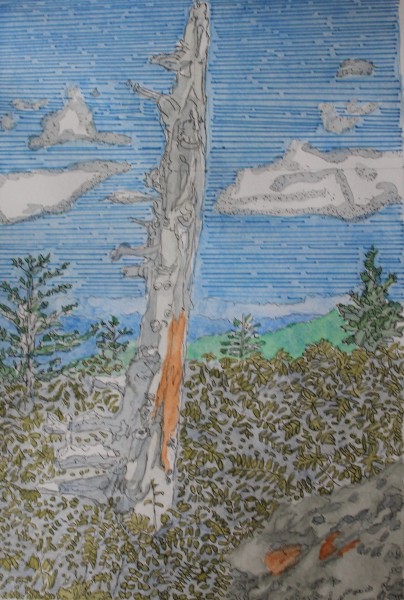

I recently went back to Haw River State Park to take photos of the royal paulownia trees there for this article. I was a little concerned that I had waited too late and that the trees might again be bare. Instead, while many of the leaves were on the ground, there were still plenty on the branches and the seed pods were just beginning to form.

My first thought on seeing the three mature royal paulownia trees there was that they looked beleaguered. The crowns appeared ill-formed, and I found the thin bark at the base of one starting to come off in a sheet. I picked up a few branches from the ground, only to find them hollow at their core. I couldn’t help but wonder if this really was the same tree I had seen in a photo taken in an Asian city. In that photo, royal paulownias line both sides of a street and their beautiful lavender flowers are in full bloom.

I had to consider the sorry shape of the trees at the park, which gave me a different perspective on this invasive. Despite the well-known aggressive growth of this species when the trees are young, these mature trees were far from thriving. The phrase “Stranger in a foreign land” came to mind, including all its implications of hardship. It may well be that in the long run the eastern United States is no better for the royal paulownia that the royal paulownia is for the eastern United States. Ultimately, the two are not well suited for each other while many rare and endangered species are perfectly matched to this ecological environment.

Though we desperately need to control the royal paulownia, I realized that it isn’t the villain of this story. Neither are the gardeners who plant the tree for esthetic reasons or the farmers who may choose to grow royal paulownia in the hopes it may provide some cash when harvested. Like myself, when I once brought home a branch loaded with the seeds of this invasive and left it on my carport for months, unknowingly endangering my small but well-loved woods, they often simply don’t know better. The challenge of controlling the royal paulownia extends far beyond managing its physical presence. As much as the physical management of this tree is important, so too is education about its devastating potential as an invasive.